Many individuals experience a noticeable increase in hunger during menopause. Hormonal fluctuations, particularly declining estrogen and rising cortisol levels, can significantly influence appetite and hunger. Estrogen plays a key role in regulating hunger, and as its levels drop, hunger signals may intensify. Similarly, elevated cortisol, often linked to stress, can further amplify appetite. These changes may prompt some individuals to wonder, “Why does hunger feel so intense during menopause?”(1)(2)(3)

Research has also shown that declining estrogen affects body composition by promoting fat accumulation, particularly in the abdominal area, and reducing lean muscle mass. These shifts not only impact how energy is used but also contribute to changes in hunger regulation during menopause.(1)

Menopausal Hunger and Eating Habits

During perimenopause and menopause, food cravings — especially for snack foods — are common. These feelings of hunger are not purely behavioral; they stem from hormonal shifts that impact appetite. Estrogen, progesterone, and cortisol interact to influence hunger signals in the brain. During perimenopause, declining estrogen levels can disrupt the balance of ghrelin and leptin, two hormones that regulate hunger and fullness. Additionally, increased cortisol levels can cause the body to seek quick energy sources, like sugar, further intensifying the feeling of hunger.(1)(2)(3)

Scientific evidence links lower estrogen levels to increased activity in brain regions associated with reward, which may explain the heightened desire for high-calorie or comfort foods. Besides this, the decline in lean muscle mass caused by hormonal changes can slow down metabolism, disrupting the balance between energy consumed and energy burned. This imbalance often increases hunger sensations.(3)

Comparing Hunger in Perimenopause and Menopause

Both perimenopause and menopause are characterized by hormonal fluctuations that influence hunger. However, the timing and intensity of these changes may differ.

Perimenopause Hunger

Perimenopause hunger is often more erratic due to fluctuating hormone levels. For instance, estrogen levels may temporarily rise before dropping again, creating unpredictable hunger patterns with periods of increased hunger interspersed with reduced or lost appetite.(1)(2)(4)

Menopause Hunger

By the time menopause occurs, consistently low hormone levels can result in a more sustained increase in appetite. This hormonal stability may cause more predictable hunger patterns, but some women find that they continue to struggle with hunger symptoms.(3)(4)

On the other hand, some individuals may experience a loss of appetite during menopause. This may stem from hormonal imbalances or gastrointestinal changes, such as slower digestion or nausea. However, underlying conditions should be assessed for significant weight loss or a sudden decrease in appetite. Consulting a healthcare provider can help determine whether additional interventions are necessary.(3)(4)

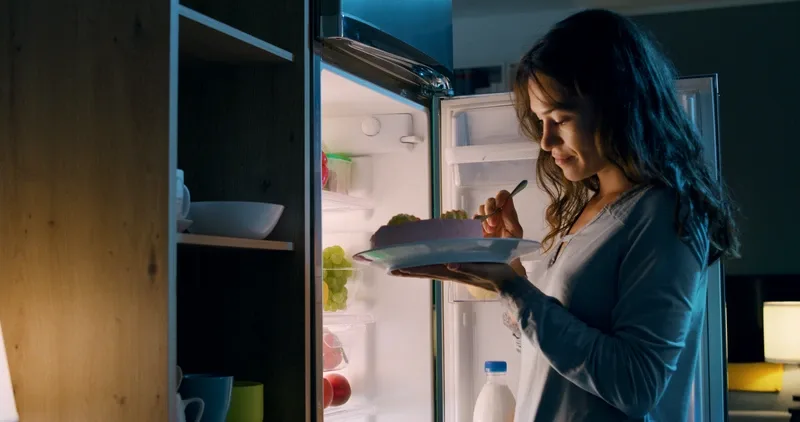

Nighttime Hunger and Hormonal Changes

Nighttime hunger is another common symptom during menopause. Cortisol levels, which typically decrease in the evening, may remain elevated in menopausal women, contributing to late-night food cravings. Additionally, disrupted sleep patterns caused by hot flashes or insomnia can affect ghrelin and leptin levels, enhancing nighttime hunger.(1)(3)

Managing Menopause Hunger

These practical strategies can help reduce menopause hunger and improve appetite control:(1)(2)(3)(4)(5)

Prioritizing Nutrient-Dense Foods

Whole foods rich in fiber and macronutrients are essential in reducing menopause-related hunger. Incorporating fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats into meals can help support overall health and manage hunger.

Establishing Consistent Meal Patterns

It’s important to pay attention to hunger cues and avoid distractions during meals. Eating meals at regular intervals throughout the day can also help stabilize blood sugar levels and reduce the intensity of hunger.

Staying Physically Active

Regular exercise helps maintain muscle mass, supports metabolic health, and aids in hunger regulation.

Staying Hydrated

Dehydration can mimic hunger, so drinking plenty of water is crucial.

Managing Stress

Techniques such as mindfulness, meditation, deep breathing, or yoga can help reduce cortisol levels and control stress-related hunger and eating.

Getting Quality Sleep

Poor sleep disrupts hunger-regulating hormones and increases hunger. Prioritizing sleep hygiene can minimize these effects.

Considering Natural Appetite Suppressants

Certain foods, such as those rich in fiber or protein, may naturally curb hunger. Foods like green tea, apple cider vinegar, and ginger may also help promote a feeling of fullness.

When to Seek Medical Advice About Hunger

While increased hunger during menopause is common, extreme or sudden changes in appetite — whether excessive hunger or significant loss of appetite — may signal underlying health issues. For example, thyroid dysfunction, particularly hypothyroidism, can lead to appetite changes and weight gain and should be ruled out. Conversely, hyperthyroidism may cause a loss of appetite and unintentional weight loss. (3)(4)

Digestive health issues, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or delayed gastric emptying, can also affect hunger and eating patterns. If appetite changes are accompanied by unexplained weight loss, persistent nausea, or other concerning symptoms, seeking guidance from a healthcare provider is essential to ensure proper diagnosis and treatment.(3)(4)

The Bigger Picture of Menopause Hunger

Menopause hunger is a natural response to the body’s hormonal changes during this stage of life. Declining estrogen, elevated cortisol, and changes in body composition all contribute to feeling hungry. However, adopting a balanced diet, maintaining an active lifestyle, managing stress, and seeking menopause treatment options can significantly alleviate these symptoms. While these strategies can be effective for many, seeking personalized medical advice is always recommended when symptoms persist or worsen.(1)(3)(4)